The UMF community mourns the loss of a venerable professor, mentor, and friend, Thomas Eastler

By Marc Glass

Several days after the passing of her husband, Susan Eastler ’82 carefully considered this question: What motivated the late professor emeritus of geology to give so much of himself to his students, the University, and the citizens of Western Maine over the past 41 years?

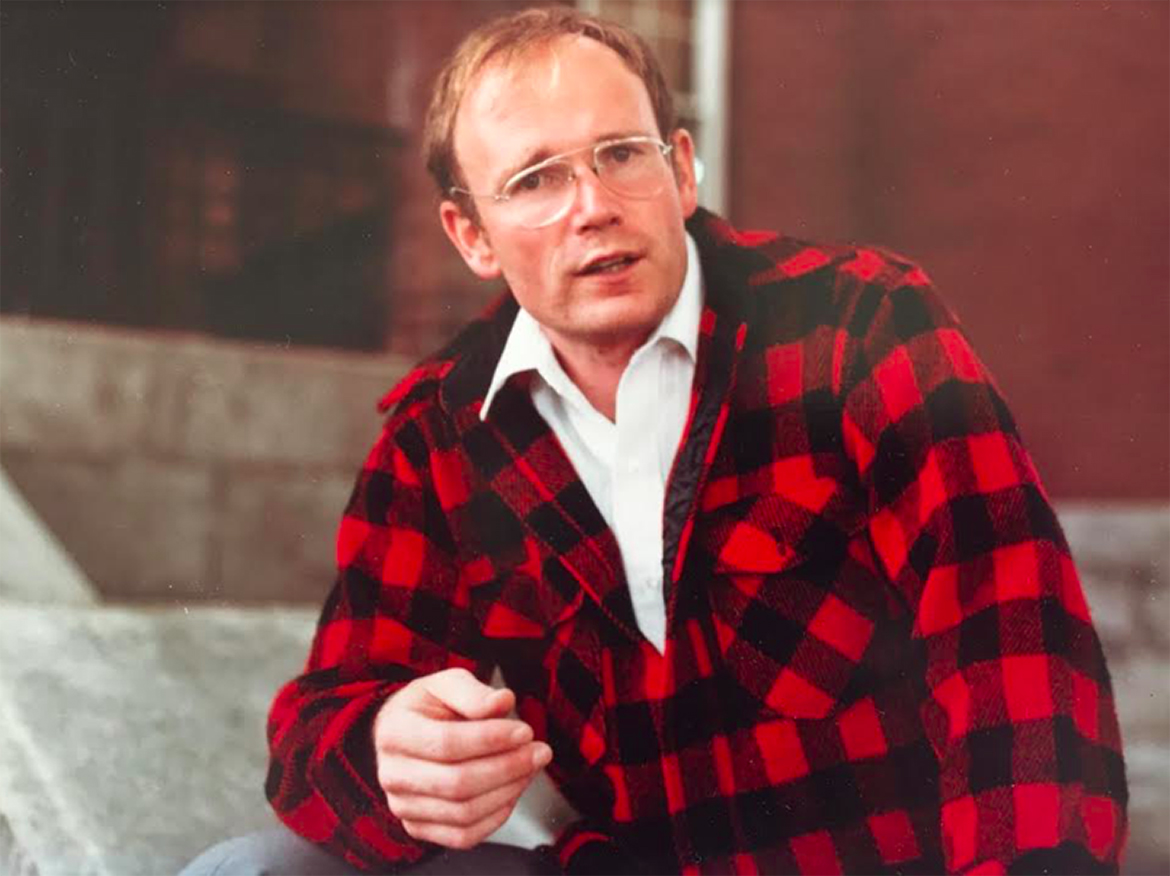

Thomas Eastler, Professor Emeritus of Geology, 1942–2018 (Photo courtesy of the Eastler Family.)

“He never turned anyone away,” said Eastler, as she welcomed Margaret Gould Wescott, the former longtime professor of dance, who came calling with home-baked treats.

“People would come to the house with rocks and ask him, ‘Would you take a look at this?’ They wanted to know if they had found a fossil or a special mineral. And he would spend many, many hours in his office talking with and helping students, sometimes to the point of even missing meals,” she said. “He loved his students. He loved the whole community. Whatever he was doing, he wanted to do it right. He gave so much of himself because that’s what he thought was required to do it the right way.”

Like the minerals, crystals, and stones that formed the foundation of his primary expertise, Tom had many brilliant facets. As noted in a eulogy from Interim President Eric Brown to the campus community, he earned his bachelor’s at Brown and his Ph.D. at Columbia. He was a race-walking coach to an Olympian — his son, Kevin — as well as Olympic-hopefuls. Throughout his civilian and military career — from which he retired, in 1996, at the rank of colonel in the U.S. Air Force Reserves — he consulted on classified security matters for the Naval Air Warfare Center and Lawrence Livermore Laboratories in California, Sandia Laboratories in New Mexico, and Raytheon in Virginia. By gubernatorial appointment, he served on the Maine Board of Environmental Protection and the Maine Low-level Radioactive Waste Authority.

He also served as chair of the area’s Sandy River Watershed Association, and a member of the town’s conservation committee and planning board. He was a gentleman farmer, as well as an authority on and ardent proponent of alternative energy.

“He was self-taught in so many of the things he enjoyed doing for people,” said Eastler, a longtime nurse practitioner specialist in Farmington. “He would spend hours researching whatever he was interested in to make sure he was doing it right. And if he didn’t know, he would call someone and ask. He would listen to anyone who could teach him.”

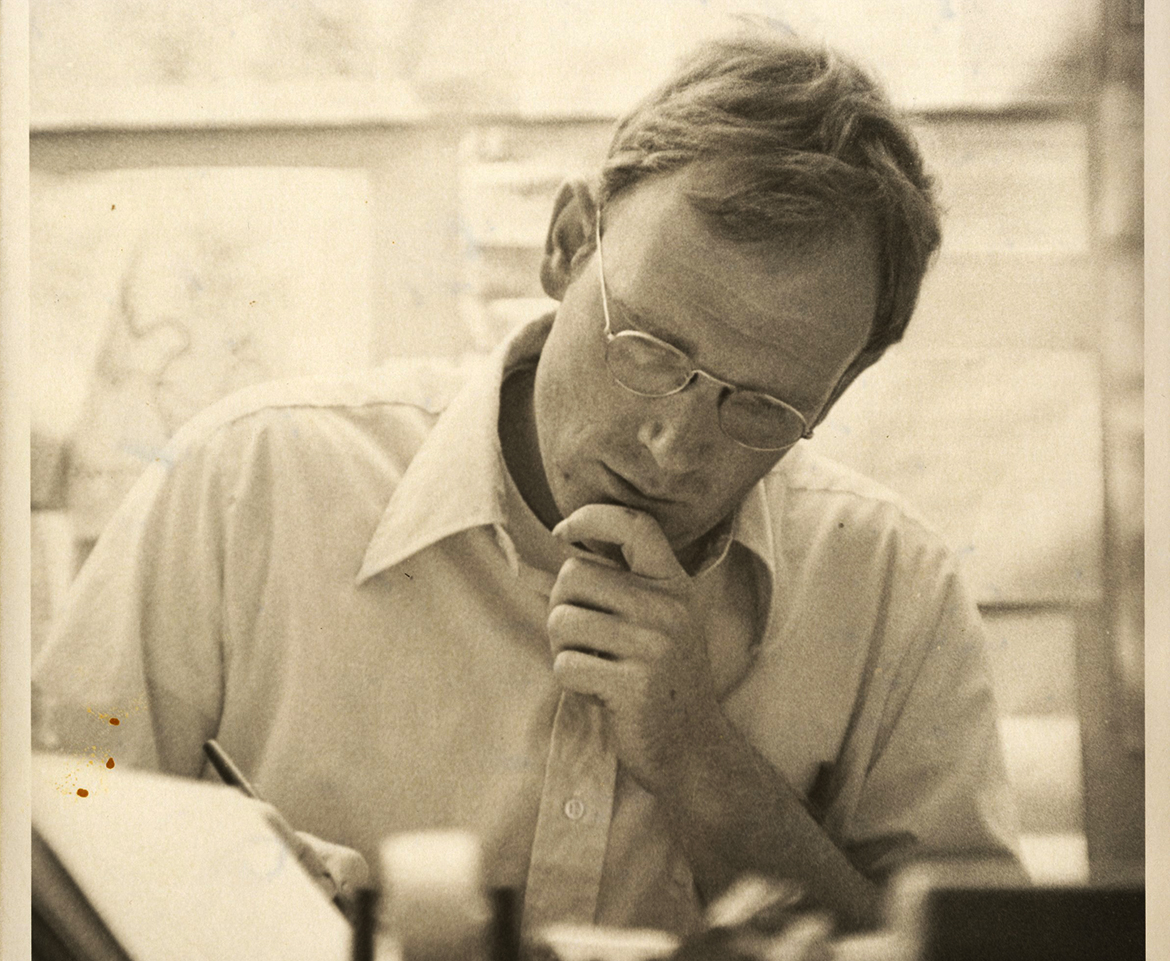

Tom, in the early days of his 41-year teaching career, in his Ricker Hall office. (Photo courtesy of the UMF Archives.)

Gretchen Eastler Fishman, Tom and Susan’s middle child (between Lauren and Kevin) and author of his widely read obituary, says that even days before his passing, her father’s interest in enlightenment was undiminished.

“He sat looking at a book on root cellaring, of all the things to choose to read at that moment. I’m not sure how much he was actually comprehending, but he was turning the pages and looking intently,” says Fishman. “It speaks volumes about how hungry he was for knowledge, right up until the end. There was no part of him that ever wanted to slow down and stop learning.”

Michael Bell ’86 is a former student who, over 30 years of friendship, came to know Tom in many of his studied roles. For Bell, one stands above all: “He was a consummate teacher.”

“He was just supercharged with an intellect and a passion for geology that you couldn’t help but gain some of his excitement for the field,” says the co-founder and president of Bell Oldow, an environmental due diligence firm based in Chelmsford, Mass. “He always wanted people to excel beyond whatever they thought possible for themselves.”

That’s how it was for Bell, from the moment he first met Tom during a senior-year-of-high-school visit to UMF. The admissions meeting with Tom was going well, recalls Bell, and he was already feeling drawn to geology more than his other academic interest, mathematics. Bell says that in Tom’s presence he even felt confident enough to bring up his personal struggles with dyslexia.

“Tom reached behind his desk, pulled out a book and said, ‘Read me that paragraph.’ I did, and he said, ‘You’re going to be fine here,’” says Bell. “That was the most powerful 30 seconds of the next 30 years of my life. He made it clear that would not be a limitation for me.”

A corporate environmental scientist who went on to earn an MBA at Suffolk University and specialize in strategic environmental risk management, Bell found a way to honor his mentor and ensure future generations of students had the resources to participate in a hallmark of Tom’s teaching — off-campus field study in geology.

“He was at the center of my experience at UMF,” says Bell, who established the Michael J. Bell Geology Field Study Fund and now serves on the University’s Board of Visitors. “Tom was a good man and friend. Having him in my life for more than 30 years was a privilege.”

“He was constantly encouraging people to earn advanced degrees and used his network to help his students take it to the next level in graduate school,” says Michael Bell ’86, lower right, pictured with Eastler and classmates atop Mount Katahdin in fall 1983. (Photo courtesy of Michael Bell ’86.)

Some of Tom’s lessons were less inspiring, at least in the moment he imparted them, but cherished in the remove of time. Such was the case, says Fishman, when her father sought to curb his family’s use of fossil fuel. For context, she explains, keep in mind that in the late ’70s McDonald’s served much of its fare in styrofoam, of which petroleum is a key ingredient.

“When I was a child, we would occasionally go there to eat, as a treat,” she says. “But he insisted that we asked for our food to be delivered in paper, rather than styrofoam, so we could do our part to cut back on using oil. It was embarrassing.”

When she protested, pointing out that no one else was asking for the change in packaging, she says her father leveled with her: “‘It doesn’t matter what anyone else is doing,’ he said. ‘You’re going to order your food to come in paper because it’s the right thing to do.’”

“His view was that it’s part of your job to live beyond yourself and do what’s right for the greater good,” she says. “He lived and practiced that every day.”

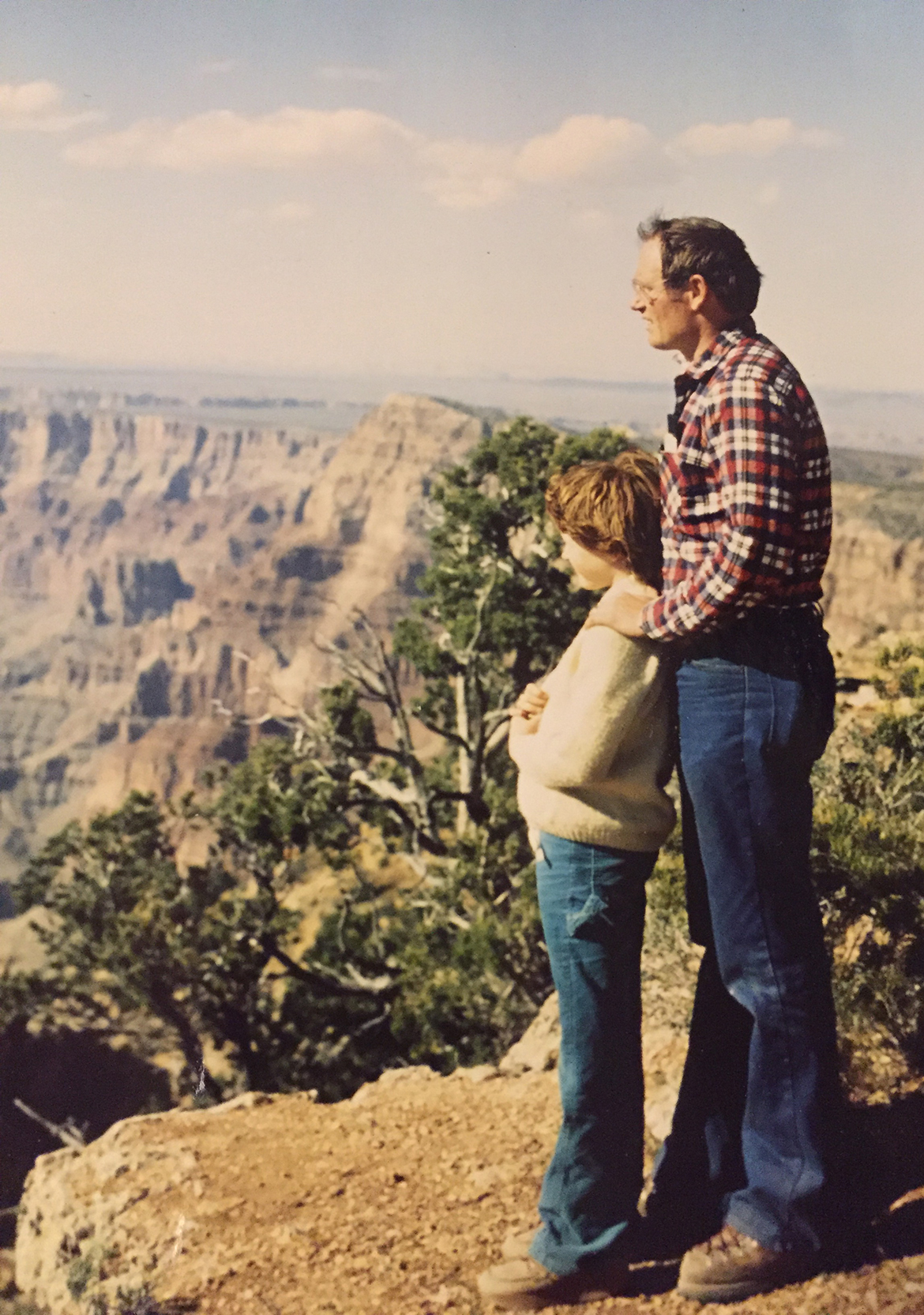

Tom and Gretchen at the Grand Canyon in late spring 1982. “We were on the UMF three-week summer geology field trip, which my father organized and led for many years,” says Fishman. “He would always take us out of school and bring us with him when he could, and we saw much of the country this way, watching him lecture to the students day after day, showing us America in a way most people never think to look at it. Those trips are some of my best childhood memories.” (Photo courtesy of Gretchen Eastler Fishman.)

A public celebration of life for Tom will be held at UMF Sunday, September 30, beginning with a 1 p.m. reception in the Dearborn Gymnasium Lobby, followed by a 2 p.m. memorial in Dearborn Gymnasium. Following the campus gathering, all are invited to Sunny View Farm, 300 Mosher Hill Road, Farmington, to place rocks for his memorial cairn.

Those wishing to honor Tom’s life are encouraged to make a gift of any size to the Thomas E. Eastler Geology Scholarship Fund. Gifts may be made online or by check to the University of Maine at Farmington, Ferro Alumni Center, 242 Main St., Farmington, ME 04938.